[Book] C++ Concurrency In Action (Second Edition)

Last Update:

Word Count:

Read Time:

El Libro

Introduction

This article is used to keep notes and summaries of the book “C++ Concurrency In Action (Second Edition)”.

The content will be continuously updated as I read through the book.

Reflection

Chapter.1 - Hello, world of concurrency

1.1 - What is concurrency

At the simplest and most basic level, concurrency is about two or more separate activities happening at the same time. You can watch football while I go swimming, and so on.

When we talk about concurrency in terms of computers, we mean a single system performing multiple independent activities in parallel, rather than sequentially, or one after the other.

Concurrency vs. Parallelism

Concurrency and parallelism have largely overlapping meanings with respect to multithreaded code. Indeed, to many they mean the same thing.

The difference is primarily a matter of nuance, focus, and intent. Both terms are about running multiple tasks simultaneously, using the available hardware, but parallelism is much more performance-oriented.

People talk about parallelism when their primary concern is talking advantage of the avaiable hardware to increase the performance of bulk data processing.

People talk about concurrency when their primary concern is separation of concerns, or responsiveness.

1.4 - Getting Started

1 | |

Every thread has to have an initial function, where the new thread of execution begins. For the initial thread in an application, this is main(), but for every other thread it’s specified in the constructor of a std::thread object——in this case, the std::thread objecct named t has the new hellow() function as its initial function.

With join(), the program possibily ends before the new thread had a chance to run.

Chapter.2 - Managing threads

2.1 - Basic thread management

Every C++ program has at least one thread, which is started by the C++ runtime: the thread running main().

1 | |

1 | |

One type of callable object that avoids this problem is a lambda expression. This is a new feature from C++11:1

2

3

4std::thread my_thread([] {

do_something();

do_something_else();

})

1 | |

In this case, the new thread associated with my_thread will probably still be running when oops exists, because you’ve explicitly decided not to wait for it by calling detach(). The program will be terminated if detach() isn’t called.

If the thread is still running, you have this scenario: the nexst call to do_something(i) will access an already destroyed variable. This is like normal single-threaded code——allowing a pointer or reference to a local variable to persist beyond the function exit is never a good idea——but it’s earier to make the mistake with multithreaded code, because it isn’t necessarily immediately apparent that this has happened.

In particular, it’s a bad idea to create a thread within a function that has access to the local variables in that function, unless the thread is guarateed to finish before the function exits.

1 | |

2.2 - Passing arguments to a thread function

1 | |

Note that even though f takes a std::string as the second parameter, the string literal is passwd as a char const* and converted to a std::string only in the context of the new thread. This is particularly important when the argument supplied is a pointer to an automatic variable, as follows:1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8void f(int i, std::string const& s);

void oops(int some_param)

{

char buffer[1024];

sprintf(buffer, "%i%, some_param);

std::thread t(f, 3, buffer);

t.detach();

}

In this case, it’s the pointer to the local variable buffer that’s passed through to the new thread and there’s a significant chance that the oops function will exit before the buffer has been converted to a std::string on the new thread, thus leading to undefined behavior. This solution is to cast to std::string before passing the buffer to the std::thread constructor:1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8void f(int i, std::string const& s);

void oops(int some_param)

{

char buffer[1024];

sprintf(buffer, "%i%, some_param);

std::thread t(f, 3, std::string(buffer));

t.detach();

}

2.3 - Transferring ownership of a thread

1 | |

First, a new thread is started and associated with t1. Ownership is then transferred over to t2 when t2 is constructed, by invoking std::move() to explicitly move ownership. At this point, t1 no longer has an associated thread of execution; the thread running some_function is now associated with t2.

The final move tansfers ownership of the thread running some_function back to t1 where it started. But in this case t1 already had an associated thread (which was running some_other_function), so std::terminate() is called to terminated the program.

You cannot just drop a thread by assigning a new value to the std::thread object that manages it.

1 | |

Likewise, if ownership should be transferred into a function, it can accept an instance of std::thread by value as one of the parameters, as shown here:1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9void f(std::thread t);

void g()

{

void some_function();

f(std::thread(some_function));

std::thread t(some_function);

f(std::move(t));

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

class scoped_thread

{

std::thread t;

public:

explicit scoped_thread(std::thread t_): t(std::move(t_))

{

if (!t.joinable())

throw std::logic_error("No thread");

}

~scoped_thread()

{

t.join();

}

scoped_thread(scoped_thread const&) = delete;

scoped_thread& operator=(scoped_thread const&)=delete;

};

struct func;

void f()

{

int some_local_state;

scoped_thread t{std::thread(func(some_local_state))};

do_something_in_current_thread();

}

1 | |

1 | |

2.5 - Identifying threads

1 | |

Chapter.3 - Sharing data between threads

If you’re sharing data between threads, you need to have rules for which thread can access which bit of data when, and how any updates are communicated to the other threads that care about the data.

Incorrect use of shared data is one of the biggest causes of concurrency-related bugs, and the consequence can be serious.

3.1 - Problems with sharing data between threads

The probles with sharing data between threads are all due to the consequences of modifying data. If all shared data is read-only, there’s no problem, because the data read by on thread is unaffected by whether or not another thread is reading the same data.

Once concept that’s widely used to help programmers reason about their code is invariants——statements that are always true about a particular data struct, such as “this variable contains” the number of items in the list.” This invariants are often broken during an update, especially if the data structure is of any complexity or the update requires modification of more than one value.

Race conditions

In concurrency, a race condition is anything where the outcome depends on the relative ordering of execution of operations on two or more threads; the threads race to perform their respective operations. This term is usually used to mean a problematic race condition.

The C++ standard also defines the term data race to mean the specific type of race condition; data races cause the dreaded undefined behavior.

Avoiding problematic race conditions

The simplest option is to wrap your data structure with a protection mechanism to ensure that only the thread performing a modification can see the intermediate states where the invariants are broken.

We can use memory model, lock-free to solve this problem.

3.2 - Protecting shared data with mutexes

Mutex stands for Mutual Exclusion.

Before accessing a shared data structure, you lock the mutex associated with that data, and when you’ve finished accessing the data structure, you unlock the mutex.

Mutexes are the most general of the data-rpotection mechanisms available in C++, but they’re not a silver bullet; it’s important to structure your code to protect in right data and avoid race conditions inherent in your interfaces.

Mutexes also come with their own problems in the form of a deadlock and protecting either too much or too little data.

Using mutexes in C++

1 | |

If one of he member functions returns a pointer or reference to the protected data, then it doesn’t matter that the member functions all lock the mutex in a nice, orderly fashion, because you’ve blown a big hole in the protection. **Any code that has access to that pointer or reference can now access (and potentially modify) the protected data without locking the mutex.

Protecting data with mutex therefore requires careful interface design to ensure that the mutex is locked befored there’s any access to the protected data and that there are no backdoor.

Structuring code for protecting shared data

Protecting data with mutex is not quite as easy as slapping an std::guard object in every member function; one stray pointer or reference, and all that protection is for nothing.

As well as checking that the member functions don’t pass out pointers or references to their callers, it’s also important to check that they don’t pass there pointers or references IN to functions they call that arent’s under you control, this is dangerous.1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33class some_data

{

int a;

std::string b;

public:

void do_something();

};

class data_wrapper

{

private:

some_data data;

std::mutex m;

public:

template<typename Function>

void process_data(Function func)

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> l(m);

func(data);

}

};

some_data* unprotected;

void malicious_function(some_data& protected_data)

{

unprotected=&protected_data;

}

data_wrapper x;

void foo()

{

x.process_data(malicious_function);

upprotected->do_something();

}

In this example, the code in process_data looks harmless enough, nicely protected with std::lock_guard, but the call to the user-supplied func function means that foo can pass in malicious_function to bypass the protection and then call do_something() without the mutex being locked.

Guidline: Don’t pass pointers and references to protected data outside the scope of the lock, whether by returning them from a function, storing them in externally visible memory, or passing them as arguments to user-supplied functions.

Just because you’re using a mutex or other mechanism to protect shared data, it doesn’t mean you’re protected from race conditions; you still have to ensure that the appropriate data is protected.

Consider the doubly linked list example. If you protected access to the pointers of each node individually, you’d be no better off than with code that used no mutexes, because the race condition could still happen——it’s not the individual nodes that need protecting for the individual steps but the whole data structure, for the whole delete operation. The easiest solution in this case is to have a single mutex that protects the entire list.

Deadlock: the problem and a solution

Imagine a pair of threads arguing over locks on mutexes: each of a pair of threads needs to lock both of a pair of mutexes to perform some operation, and each thread has one mutex and is waiting for the other. Neither thread can proceed, because each is waiting for the other to release its mutex. This scenario is called deadlock, and it’s the biggest problem with having to lock two or more mutexes in order to perform an operation.

The common advice for avoiding deadlock is to always lock the two mutexes in the same order.

The C++ Standard Library has a cure for this in the form of std::lock——a function that can lock two or more mutexes at once without risk of deadlock.

1 | |

First, the arguments are checked to ensure they are different instances, because attempting to acquire a lock on std::mutex when you already hold it is undefined behavior (A mutex that does permit multiple locks by the same thread is provided in the form of std::recursive_mutex.).

Then, the call to std::lock() locks the two mutexes, and two std::lock_guard instances are constructed and, one for each mutex.

The std::adopt_lock parameter is supplied in addition to the mutex to indicate to the std::lock_guard objects that the mutexes are already locked, and they should adopt the ownership of the existing lock on the mutex rather than attempt to lock the mutex in the constructor.

C++17 provides additional support for this scenario, in the form of a new RAII termplate, std::scoped_lock<>. This is exactly equivalent to std::lock_guard<>, except that it is a variadic template, accepting a list of mutex types as template parameters, and a list of mutexes as constructor arguments. The mutexes supplied to the constructor are locked using the same algorithm as std::lock, so that when the constructor completes they are all locked, and they are then all unlocked in the destructor.1

2

3

4

5

6

7void swap(X& lhs, X& rhs)

{

if(&lhs==&rhs)

return;

std::scoped_lock guard(lhs.m,rhs.m);

swap(lhs.some_detail,rhs.some_detail);

}

This example uses another feature added with C++17: automatic deduction of class template parameters.

This line is equivalent to the equivalent to the fully specified version:1

std::scoped_lock<std::mutex, std::mutex> guard(lhs.m, rhs.m);

The existence of std::scoped_lock means that most of the cases where you would have used std::lock prior to C++17 can now be written using std::scoped_lock, with less potential for mistakes.

You have to rely on your discipline as developers to ensure you don’t get get deadlock. This isn’t easy: deadlocks are one of the nastiest problems to encounter in multithreaded code and are often unpredictable, with everything working fine the majority of the time.

Futher guidlines for avoiding deadlock

Deadlock doesn’t only occur with locks. You can create deadlock with two threads and no locks by having each thread call join() on the std::thread object for the other. In this case, neither thread can make progress because it’s waiting for the other to finish.

The guidlines for avoiding deadlock all boil down to one idea: don’t wait for another thread if there’s a chance it’s waiting for you.

- Avoid nested locks:

Don’t acquire a lock if you already hold one. If you stick to this guidline, it’s impossible to get a deadlock from the lock usage alone because each thread only ever holds a single lock. You should still get deadlock from other things (like the threads waiting for each other), but mutex locks are probably the most common cause of deadlock. - Avoid calling user-suplied code while holding a lock:

This is a simple follow-on from the previous guidline. Because the code is user-supplied, you have no idea what it could do; it could do anything, including acquiring a lock. - Acquire locks in a fixed order:

If you absolutely must acquire two or more locks, and you can’t acquire them as a single operation withstd::lock, the next best thing is to acquire them in the same order in every thread. - Use a lock hiearchy:

Although this is a particular case of defining lock ordering, a lock hierarchy can provide a means of checking that the convention is adhered to at runtime. The idea is that you divide your application into layers and identify all the mutexes that may be locked in any given layer. - Extending these guidlines beyond locks:

Deadlocks also occur with any synchronization construct that can lead to a wait cycle.\

If you’re going to wait for a thread to finish, it might be worth identifying a thread hierarchy, so that a thread waits only for threads lower down the hierarchy. One simple way to do this is to ensure that your threads are joined in the same function that started them.

Flexible locking with std::unique_lock

Once you’ve designed your code to avoid deadlock, std::lock() and std::lock_guard cover most of the cases of simle locking, but sometimes more flexibility is required.

std::unique_lock provides a bit more flexibility than std::lock_guard by relaxing the invariants; an std::unique_lock instance doesn’t always own the mutex that it’s associated with.

You can pass std::adopt_lock as a second argument to the constructor to have the lock object manage the lock on a mutex, you can also pass std::defer_lock as the second argument to indicate that the mutex should remain unlocked on construction.

1 | |

Using std::unique_lock and std::defer_lock, rather than std::lock_guard and std::adopt_lock.

std::unique_lock objects could be passed to std::lock(), because std::unique_lock provides lock(), try_lock(), and unlock() member functions.

Transferring mutex ownership between scopes

Because std::unique_lock instances don’t have to own their associated mutexes, the ownership of mutex can be transferred between instances by moving the instances around.

Locking at an appropriate granularity

The lock granularity is a hand-waving term to describe the amount of data protected by a single lock. A fine-grained lock protects a small amount of data, and a coarse-grained lock protects a large amount of data.

3.3 - Alternative facilities for protecting shared data

Chapter.4 - Synchronizing concurrent operations

Sometimes you don’t just need to protect the data, you also need to synchronize actions on separate threads. One thread might need to wait for another thread to complete a task before the thread can complete its own, for example. In general, it’s common to want a thread to wait for a specific event to happen or a condition to be true.

4.1 - Waiting for an event or other condition

If one thread is waiting for a second thread to complete a task, it has several options. First, it could keep checking a flag in shared data (protected by mutex) and have the second thread set the flag when it come pletes the task. This is wasteful on two counts: the thread consumes valuable processing time repeatedly checking the flag, and when the mutex is locked by the waiting thread, it can’t be locked by any other thread.

1 | |

In the loop, the function unlocks the mutex before the sleep, and locks it again afterward so another thread gets a chance to acquire it and set the flag.

This is an improvement because the thread does not waste processing time while it’s sleep, but it’s hard to get the sleep period right.

The third and preferred option is to use the facilities from the C++ Standard Libaray to wait for the event itself.

Waiting for a condition with condition variables

The Standard C++ Library provides two implementations of a condition variable: std::condition_variable and std::condition_variable_any. Both of these are declared in the <condition_variable> library header.

In both cases, they need to work with a mutex in order to provide appropriate synchronization the former is limited to working with std::mutex, whereas the latter can work with anything that meets the mimimal criteria for being mutex-like, hence the _any suffix.

std::condition_variable_any is more general, there’s the potential for additional consts in terms of size, performance, or OS resources, so std::condition_variable should be preferred unless the additional flexibility is required.

1 | |

- You have a queue that’s used to pass the data between two therads.

- Note that you put the code to push the data onto the queue in a smaller scope, so you notify the condition variable after unlocking the mutex.

- On the other side of the fence, you have the processing thread. This thread first locks the mutex, but this time with a

std::unique_lockrather than astd::lock_guard. The reason isstd::unique_lockis reusable. The waiting thread must unlock the mutex while it’s waiting and lock it again afterward, andstd::lock_guarddoesn’t provide that flexibility.

Chapter.5 - The C++ memory model and operations on atomic types

This chapter will start by convering the basic of the memory model, then move on to the atomic types and operations, and finally cover the various types of synchronization available with the operations on atomic types.

5.1 - Memory model basic

Objects and memory locations

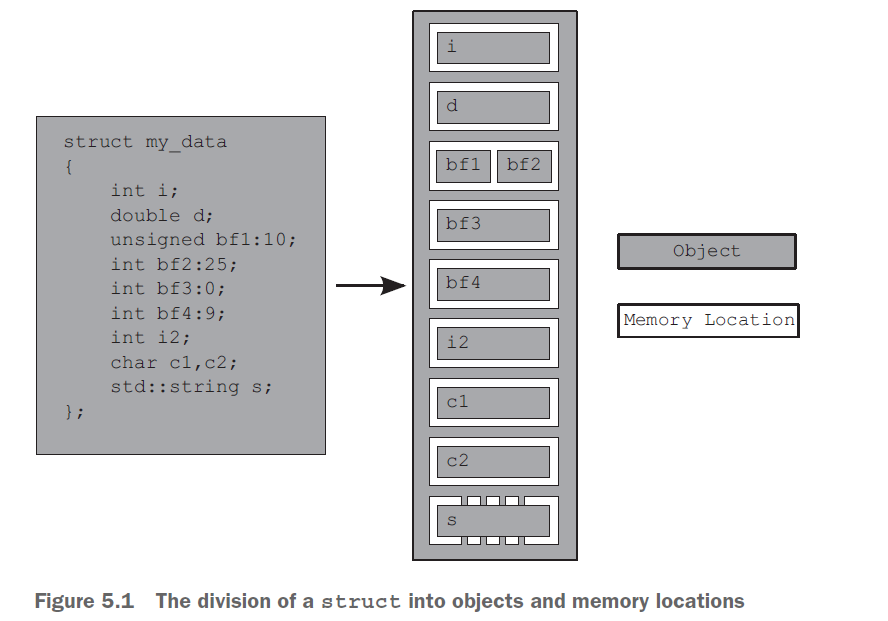

The C++ Standard defines an object as “a region of storage”, although it goes on to assign properties to these objects, such as their type and lifetime.

Whatever its type, an object is stored in one or more memory locations. Each memory location is either an object (or sub-object) of a scalar type such as unsigned short or my_class* or a sequence of adjacent bit fields. If you use bit fields, this is an important point to note: though adjacent bit fields are distinct objects, they’re still counted as the same memory location.

There are four important things to take away from this:

- Every variable is an object, including those that are members of other objects.

- Every object occupies at least one memory location.

- Variables of fundamental types such as

intorcharoccupy exactly one memory location, whatever their size, even if they’re adjacent or part of an array. - Adjacent bit fields are part of the same memory location.

Objects, memory locations and concurrency

If two threads access separate memory locations, there’s no problem: everything works fine. On the other hand, if two threads access the same memory location, then you have to be careful.\

If neither thread is updating the memory location, you’re fine; read-only data does not need protection or synchronization.

If either thread is modifying the data, there’s a potential for a race condition.

Solutions:

- mutexes.

- Synchronization properties of atomic operations.

If two threads access the same memory location, each pair of accesses must have a defined ordering.

If there’s no enofrced ordering between two accesses to a single memory location from separate threads, one or both of those accesses is no atomic, and if one or both is a write, then this is a data race and causes undefined behavior.

Modification orders

If you do use atomic operations, the compiler is responsible for ensuring that the necessary synchronization is in place.\

This requirement means that certain kinds of speculative execution ain’t permitted, because once a thread has seen a particular entry in the modification order, subsequent reads from that thread must return laster values, and subsequent writes from that thread to that object must occur laster in the modification order.

5.2 - Atomic operations and types in C++

An atomic operation is an indivisible operation. You can’t observe such an operation half-done from any thread in the system; it’s either done or not done.

If the load operation that reads the value of an object is atomic, and all modifications to that object are also atomic.

The flip side of this is that a non-atomic operation might be seen as half-done by another thread. If the non-atomic operation is composed of atomic operaitons (for example, assignment to struct with atomic members), then other threads may observe some sbuset of the constituent atomic operation as complete, but others as not yet started, so you might observe or end up with a value that is a mixed-up combination

of the various values stored.

The standard atomic types

The standar atomic types can be found in the <atomic> header. All operations on such types are atomic, and only operations on these types are atomic in the sense of the language definition, although you can use mutexes to make other operation appear atomic.